While I am all in favor of a healthy respect for weather among VFR pilots, I also believe there could be excessive fear instilled during the training process that makes an inadvertent encounter with IMC more dangerous than it needs to be.

Having gotten my private-pilot certificate in 1981, I was a VFR-only pilot for about three years before starting work on my instrument rating. My prime motivation was all those flights scrubbed due to a thin cloud layer or just the threat of a narrow patch of weather blocking the way. I had stretched my VFR cross-country envelope with my little Grumman Trainer on trips from my home in New England as far as Key West, Florida, and found myself grounded en route a few too many times for my liking. My dead reckoning VFR navigation and map reading were functional, as far as they went; a necessity in my case, since the Grumman’s factory navigation equipment was limited, to say the least.

I had further motivation when I was hired as an editor at FLYING Magazine in the mid-1980s. Editor-in-Chief Richard Collins was a passionate instrument flyer, and when you worked for him, getting yourself IFR-rated was virtually a foregone conclusion. So, I got my instrument rating, but even so, most of my flying in my own airplane remained VFR-centric. The Grumman’s limited range was as big a factor as the avionics, though I had at least managed to upgrade from the lone Narco Escort 110 in the panel to a King KX170B and a fancy Mode-C transponder. It seems hard to imagine now, but the wonder of GPS navigation was not yet a glimmer in most aircraft owners’ eyes.

From the beginning of my flying lessons, I was always conscious of the ever-present specter of succumbing to “continued VFR into IMC.” As VFR pilots, we were told repeatedly that we would last only a few harrowing moments in the soup before tumbling into irreversible loss of control. I trained and practiced the routine of gingerly executing a shallow 180-degree turn to escape the jaws of death that lurked within the clouds. Even earning the instrument rating didn’t do enough to calm that fear. The training process did not encourage flying in actual IFR conditions, so virtually all of my “experience” at flying on the gauges was under a hood. It was hard to balance the feeling of confidence that was supposed to come from the instrument rating with the ingrown dread of so many years of avoiding clouds as if they were filled with hungry trolls just waiting for me to trespass.

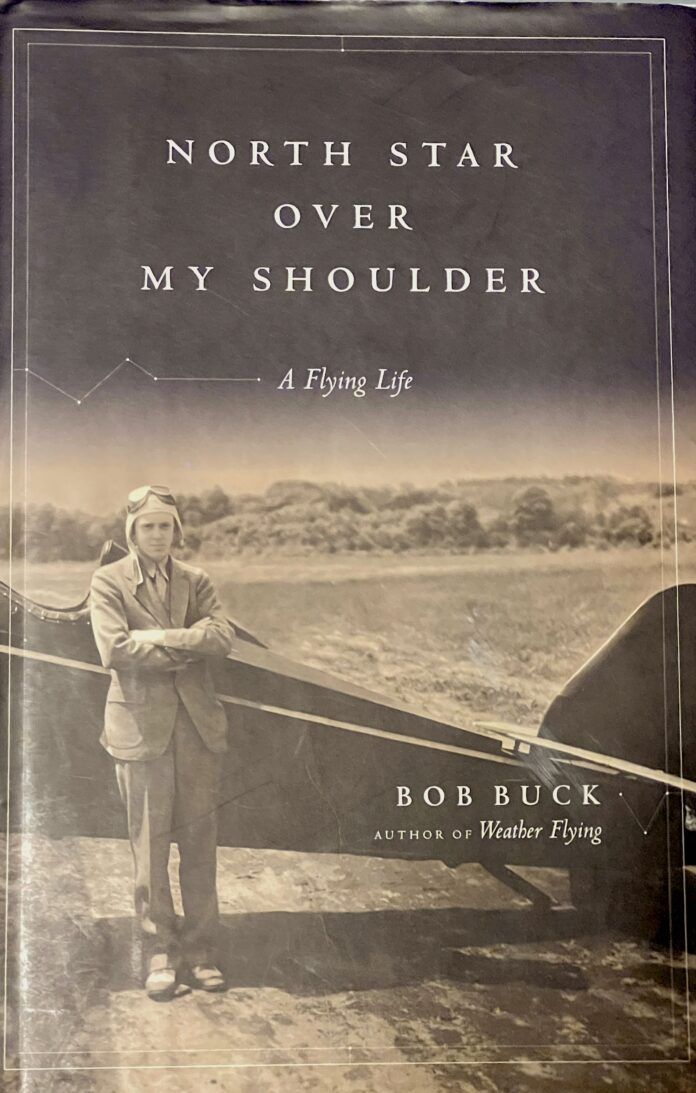

That’s why it was almost a shock to my system when I read career pilot (and accomplished writer on weather flying) Bob Buck’s memoir, North Star Over My Shoulder. He described the first time he flew on instruments—just turn-and-bank, airspeed, and compass—on a 1930 trip from New Jersey to New Hampshire in his Pitcairn Mailwing biplane. And he was a teenager at the time! “At 3,000 feet, I leveled off, pulled the power back to cruise, and dared to look around—there was whiteness everywhere, not a break in it, no ground, no blue sky, just white above, below, all around. But the instruments said we were steady-on, and despite the worry, a feeling of comfort edged its way in. I was well above the ground, not down near trees and hills trying to hedge-hop in bad visibility wondering where the next dangerous obstruction was—no, up here I was safe. I slid back further in the seat and gradually relaxed, felt as though the whiteness was protecting me, that the world now was the snug cockpit and the instruments on the panel that translated how the airplane was doing in space. The airplane and I were released from the earth, not bound to it—we were of the sky only, truly flying.”

Wow. I had never, ever, associated flying in solid cloud with “a feeling of comfort.” Pardon the pun, but it opened my eyes to a new way of looking at flying blind. I thought about Bob Buck’s words the first time I sank into a cloud layer on an instrument approach on my own. He helped reassure me that I was “steady-on.” And while I continue to believe it’s healthy to instill a reasonable fear of cloud into VFR pilots, I wonder if it might not also be a good idea to balance that fear with some of the fascination that Bob Buck experienced on his first instrument flight.

God bless Bob Buck and the north star over his shoulder. Regulation and the threat of violations were not a concern of his back then. I know that feeling from a different lifetime of my own except it was the southern cross over my shoulder, a well wound clock, the ability to hold a heading, a good knowledge of MOCA, and the hope that the destination airstrip was free of God’s 2 and 4 legged creatures. That land was theirs before it temporarily became mine for a short and bumpy rollout.

IT’s possible to survive inadverdent IMC without an instrument rating but the odds are well stacked against you. Penetrating a puffy CU for 15 seconds is not the same as sitting in a stratus deck for 30 minutes hoping to find a sucker hole to spiral down through. Romantic though it may seem, fiddling around with IMC is often a one way trip and there is no reset button. Think pretty hard before you try it.

I know the feeling described by Mr. Buck, I read the book a while back. My most memorable flying moment was a short IMC trip from KEUG to S21, with a VOR step down approach in blowing snow in a Cessna 303. Everything worked on the airplane and I was able to match that performance. Boots, prop heat, windshield heated patch, hand flying to the King NAVCOM on a HSI and DME from the VOR. Nothing but the instruments to see except snow flakes in the strobes. Then finally the VASI and a landing on hard pack snow.

I pulled off with the engines at idle and my first thought was: I want to do that again.

I’ll never forget it.

The same can be said about the alleged impossible turn. Sometimes there is no choice. Deviate 10 degrees left, or, right after departure and you will immediately vaporize. 😱

I teach my VFR students, that inadvertent IMC is not likely to be because POOF there’s a cloud, and suddenly you’re in it – I hope that I’ve instilled the judgement not to depart when it’s IFR – but flying VMC in low vis perhaps on a cross country, can be problematic. I talk about how to handle that situation – to confess, and work with ATC. While the POOF scenario, is easily exited with a 180 degree turn, the more likely scenario will require more skills. I have my VMC students regroup under the hood, and track to a waypoint (VOR in the old days,) so as to encounter VFR conditions. The weather shouldn’t be so horrible that this is not possible, or one shouldn’t have taken off in the first place. I require this as a minimum.

I never met Bob Buck, although I was at TWA for the last 10 years of his career. The senior captains I flew with early in my career all knew him. He was held in very high regard.

If all you have to do is keep the wings level then IFR flying is simple. But when you start having to look for frequencies to talk to ATC or look at your navigation without having an autopilot to keep the wings level, then there is a high probablity that your wings level flight may turn into a dangerous attitude, just like the JFK Jr. plane crash in 1999 at Martha’s Vineyard. And there is always the potential mid air risk that you have created with out an ATC clearance, depending upon what airspace you are in.

More than once during the years I have had to explain to an impatient controller that it’s just me up here and no autopilot, so please ease off & provide a vector or two while I sort out that total clearance revision.

Yup, Every airplane is “Radar Vector Equiped”

I am with Bob Buck. I was lucky to learn to fly with my father and spent a fair bit of time in IMC prior to ever going solo. A few days after I earned my instrument rating in 1976, a winter storm rolled into SoCal. I scheduled the airplane and spent about 5 hours doing tower-enroute all over SoCal. It was FUN! Best video game ever! Do it right and you get a runway!

Later, when my wife was learning to fly, we were headed up to Portland to pick up her son. Un-forecast weather popped up along the way. I was in the right seat and she was in the left. I asked her, “So, you have a choice. You can turn back and remain in VFR conditions, or we can ask for a pop-up IFR clearance and continue. Your choice.” She opted to continue IFR. We got the clearance and descended into the clag. She immediately panicked. “I can’t do this,” she hollered. (Meantime I am subtly keeping the wings level.) “Yes you can. You just completed your hood work and you did just fine. Get your scan going and fly the airplane.” After about 5 minutes I could see the blood flow coming back to her hands. After about 10 minutes she said, “This isn’t that hard.” A few minutes later it was, “Oh, this is easy.” I then let her fly AND handle comms with ATC. She flew all the way to the FAF where I took over and flew the ILS to landing.

A couple weeks later we were headed home from work in our Grumman Tiger. She flew into an unseen cloud. >POOF< ground and sky contact disappeared. It took her about 10 seconds to realize what had happened. (I had already transitioned to the gauges from the right seat.) She started to panic again I said, "Well, where were you last in VMC? So why don't you go back there?" Oh. Easy. Turn around and leave the cloud. She did. All good.

Point here is, it is frightening until you do it. Do it and it becomes familiar. Once familiar it is no longer frightening. God bless the CFI-Is who take their students into IMC and help them to build their confidence.

I’ve been a VFR-only pilot for about 31 years. In that time I’ve flown inadvertently into IMC multiple times. Once, intentionally because I was stuck on top of a stratus layer. I didn’t die on any of those occasions. I can see the allure of IMC flying but truth be told, I fly to look at things. Not really to travel. However, I don’t fly around looking for clouds to fly into either. That all being said, inadvertent IMC is definitely not a death sentence.

I was only a private pilot, but had been around aviation (Navy 4 years and working for flight school/FBO) for 6 years. On May 5, 1976 I had flown 8819G (C-150) from Renton, WA (KRNT) to Corvallis (KCVO) to pick up my friend Nancy for an airplane ride down to Myrtle Creek (16S). I liked to fly in the middle of the day, but time slipped by and it was nearing sundown when we launched for the 90 nm trip back to Corvallis. We flew into a cloud about 15 miles from home. I almost immediately

did a 180 and popped back out. I credit my instructors with my knowing what to do and how to do it safely when the “soup” shows up unexpectedly.

You’ve so accurately captured my own feelings of nervousness and anxiety when penetrating IMC with this article. But over the years as I’ve had to navigate through real IMC on IFR flights, I’ve also experienced that weird reassurance that the panel in front of me was keeping me safe. I call it “IMC Zen”. All that said though, flying in IMC, especially if you don’t do it very often, requires an extreme amount of focus and calm, that only come from practice and proficiency. It is not for the faint of heart or the unprepared.

Fear is not the reaction we want when an accidental entry to IMC occurs. I have been flying for 32 years, strictly VFR. I have entered IMC twice. I immediately went to the panel, but did not do anything else immediately. I then did a careful 180 and then when completed I did a slow descent. That’s how you do it.

A couple decades ago, I was planning to go to AZ (from AK) to “go get” my instrument rating, knock it out at one of those beautiful VFR everyday training schools that boasted a 10 day rating. Dave K, a friend of mine, and Fed Ex pilot for his day job, encouraged me to alter my training plan and learn where some good hard IMC would be part of the learning magic. That was probably the best advice I ever got. I went to Oregon instead, in the spring, to have clouds but minimal potential for icing. I trained with Julie T, an awesome CFII, one on one for a couple weeks. We even picked up unforecast icing a couple times to add to my learning journey. I recall that “feeling of comfort” especially on the day we were descending out of it and the windshield was completely frosted over, and i comfortably went back to my gauges & used my peripheral vision until the frost cleared shortly after clearing the clouds.

Bob Buck’s memoir excerpt emphasizes comfort in IMC (when spatial disorientation has been mastered/eliminated), “as though the whiteness was protecting me”.

For prolonged, en route IMC (as distinct from momentary IMC) …

flying NJ to NH, with limited 1930s-era weather information, was it luck that that did not contribute other threats typical in IMC?

(for Northeast: Summer/embedded TS, Winter/ice, LIFR, etc.)

Prior to 1927 there were no regulations for aircraft certification in the US. The first pilot certification was in 1928. So Lindbergh and many of the pilots of that era had no instrument rating and probably had the same self training as Buck.

When Buck got his private certificate the minimum age was 16. That requirement lasted only a year and was raised to 17.

Lindbergh had only a turn and bank and a special compass for the Paris flight.

My first instrument training was under the hood with just a turn and bank. I knew of one case where a pilot took and passed an instrument check ride in a Cessna 140 with only turn and bank, directional gyro and low frequency radio. A few weeks later he was hired as copilot for an airline DC3. A very different world.

My favorite books are Langwiesche’s “I’ll Take The High Road” and Bucks “North Star”.

As it was lent to me, may I suggest “the Flight of the Mew Gull” to get an insight into the emerging world of flight. It was the real thing.

As a CFI-CFII, I would not encourage violating cloud separation and visibility minimums. I agree, unexpected IMC poses real dangers, but overemphasizing fear can do more harm than good. It’s better to start with clear explanations of how inadvertent flight into IMC affects interactions with ATC, other aircraft, and terrain and the importance of staying calm and exiting the situation by reference to instruments thoughtfully and safely. Good practice (training) will make you better! Great topic. Read the book.

One of my favorite instrument books in my aviation library is Bob Buck’s “Weather Flying”. It’s been updated to reflect modern avionics by his son.

For some reason, I have never feared being in the clouds. I had several great instructors who put me in the clouds early on, so I’ve always felt pretty comfortable, and mostly that’s been hand flying—no autopilot. So when I was instructing, both basic and advanced students, I also encouraged them to take their lessons in real IMC. It’s a whole lot different from flying under the hood.

“Just trust your instruments…”

How can I possibly trust my instruments? How do I know my instruments aren’t lying to me?

Part of learning to fly instruments goes into the ‘systems’ of the different instruments, how and why they work. There is science behind how gyros work, and having scientific knowledge helps build faith in what you are working with.

Ah, yes, but we live in a society and a time where people’s gut feelings are at variance with scientific evidence. So why should I trust my instruments? I have an alternative theory on what’s really going on with my airplane, which way I should be going, which way is up…